Exhibition Review, written by Trevor Bishai for Musée Magazine

Plate 124, Patagonia, Chile, 2019. Archival pigment print

The German-born visual artist Renate Aller has long been interested in the intersections between memory and landscape. Made up of large-scale images of remote natural forms such as Patagonian glaciers and the Himalayan mountains, her latest series, The Space Between Memory and Expectation, shows how interconnected distant environments across the world are, and in doing so references several ideas about liminality, time, and space.

Plate 79, New Mexico, USA, 2012. Archival pigment print

In the tradition of landscape photography, Aller’s images are quite unconventional. While they are no doubt landscapes, they break convention in a twofold way. First, the carefully chosen subject matter has a very homogenous color palette. Where we are used to seeing a mass of natural colors in fine detail in traditional landscapes, Aller’s images are highly monochromatic, depicting glaciers and skies with a highly similar collection of pale blue tones. The ocean, which appears in several of her works, never takes on its quintessential aqua-green hue; rather, it is cast nearly in grayscale. Instead of depicting landscapes with many colors, Aller pushes us to examine the ever-so-subtle variations in the natural hues, such as the way the glacier’s shadows deepen its turquoise shades in “Plate 129,” or the way the sky alludes to Mark Rothko in the gradual shifting of tones in “Plate 70.”

Plate 129, Patagonia, Chile, 2019, Archival pigment print

While their color palettes are quite uniform, her images in no way lack the detail normally associated with large-scale landscapes. Five feet wide and over three feet high, each print is loaded with minute variations in form and color and are so large that such details are highly inviting, urging the viewer to take a closer look.

Aller’s landscapes are also unique in their elusiveness. Intentionally excluding any details that would give the viewer a sense of place or setting, her landscapes border on the abstract. This is especially evident given the absence of a sense of scale. Aller’s images include no benchmark objects such as trees, buildings, or people, with which we would ordinarily be able to gauge how large the natural forms are or how close the photographer is standing to them. Rather, we are left wondering both where we are and how far away these forms are.

Aller herself writes of a certain amount of “disembodiment” associated with such a loss of the viewer’s sense of scale, and this speaks volumes to the idea of liminality, which her series directly interrogates. The Space Between Memory and Expectation references liminal spaces, such as the interim period between two events or phases of life, during which one does not feel like they are in either of these phases. After memory elapses, but before expectation begins, there is a space in which “apparently nothing happens, but without which no change could happen.” In the liminal state, a period of both calm and transition, the individual attempts to make sense of their peculiar situation, and we are thrown into a similar condition when standing in front of Aller’s photographs. Leaving no visual clues to grasp onto for a sense of scale or size, the viewer is left in a steady state of wonder.

Plate 107, German Alps, 2020. Archival pigment print

These liminal spaces are also created through careful arrangement and layout of the works. Each image is intentionally paired with another to engender a sense of continuity—to make it seem like all the images describe one continuous landscape. What is interesting about this, however, is that many of the images’ counterparts portray very different natural forms from one another. For example, we see an image of the Atlantic Ocean taken from the United States right next to a photograph of a glacier in Patagonia. There is sharp contrast here in terms of composition—the tranquil ocean imposes a sense of silence and calm next to a domineering glacier. But due to their similarities in terms of color and lack of the sense of scale, we get the sense that we are observing one continuous natural form. Melting from glacier to ocean, and evaporating to meet the mountaintops as snow, the water cycle connects such distant environments. But even if we knew nothing about the water cycle, Aller’s images blend into a unique whole, one filled with motion and change.

Plate 70, Atlantic Ocean, USA, 2010. Archival pigment print

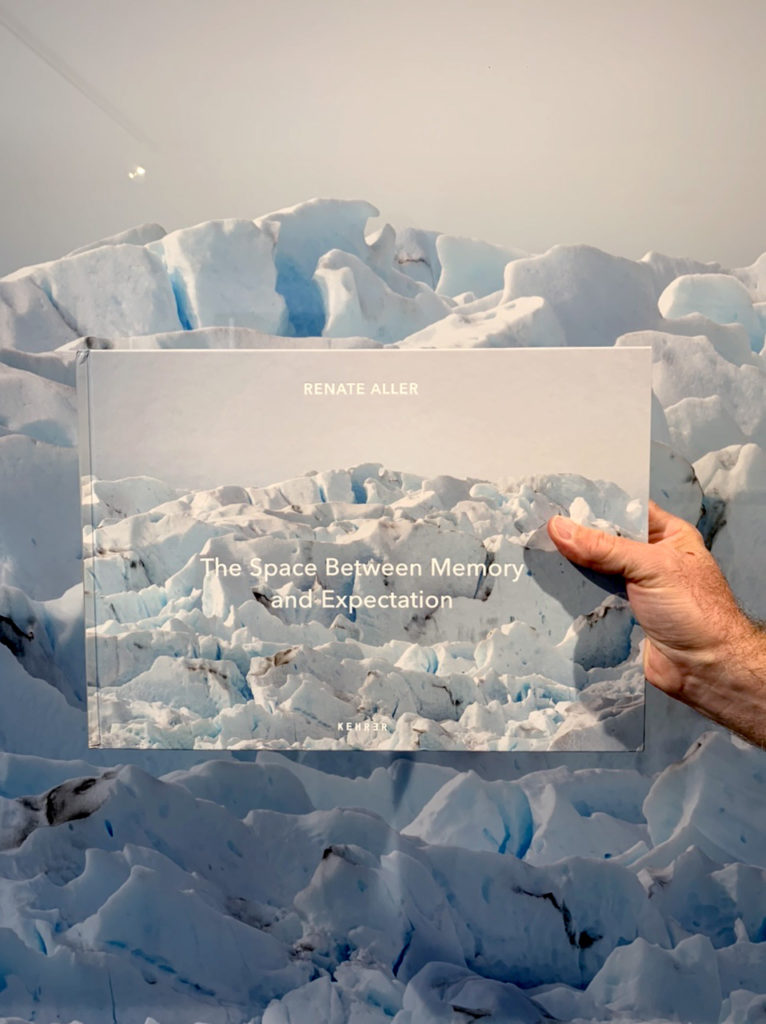

Aller’s series has also recently been published as an eponymous photobook by Kehrer Verlag in Germany with essays by Makeda Best, Curator Harvard Museums and Courtney J Martin, Director of the Yale Centre for British Art.

Renate Aller, monograph published by Kehrer Verlag, with essays by Makeda Best, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Harvard Art Museums, and Courtney J Martin, director of the Yale Center for British Art

- Hardcover

- ca. 34 x 25 cm, 144 pages, 64 color images

- ISBN: 978-3-96900-027-4