Rose B. Simpson is always working hard in the studio. This article talks about what she is up to in early 2020, and how the Wheelwright Museum solo show in 2018-19 introduced her work and vision to a whole new group of people. LINK to New Mexican, please copy and paste.

Flying high: Artist Rose B. Simpson

It’s a mild winter day in late January, and Rose B. Simpson, dressed in a dark sweatshirt and jeans, is busy at her potter’s wheel, just starting on a new piece. Under her practiced hands, the rectangular clay slab quickly takes on cylindrical form. “I have a running joke with a friend of mine where I say, ‘I have to go dig clay,’ ” says Simpson, who purchases 50-pound bags of it from a company in Albuquerque — unlike some of her Santa Clara Pueblo relatives, who gather clay by hand. “So I go to the store and get out my cornmeal and throw it, and say my prayers,” she jokes, tossing up her hand as though making an offering. “What I’m asking my clay to do requires it to be really high-fired. I need it to be really dense and strong because I ask a lot of it.”

It’s early in the day and Simpson, 36, a recipient of the Women’s Caucus for Art’s 2020 President’s Art & Activism Award, isn’t wasting any time. At her Española studio, she’s trying to get a head start on a project she plans to complete for the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Colorado for a two-week residency in early March. The work she’s doing now is for an exhibition slated to open in May at The School, an old schoolhouse in Kinderhook, New York, that’s managed by the Jack Shainman Gallery.

The studio is attached to her mother Roxanne Swentzell’s Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute, at Santa Clara Pueblo. It’s a cramped space, no larger than a one-car garage, stacked with bags of pale, flesh-colored clay, and the air is perfumed with its earthy aroma. Bottles and tubes of glue and acrylic paint crowd the shelves next to Simpson’s framed master’s degree from the vaunted Rhode Island School of Design. (“Conferred with honors,” it reads in a stately script.) The cement floor is gouged with deep scars that Simpson explains are from the time when her uncle, sculptor Michael Naranjo, used the studio. “He was using an angle grinder on his stonework in here,” she says. “And he’s blind.”

In one corner rests an old squat kiln, about waist high, with room enough for clay pieces no larger than 26 inches. That’s pretty astounding, considering that much of Simpson’s work is life-sized or larger. “You made everything with this kiln?” asked an incredulous Helen Molesworth, the curator of the New York show, when she saw it. Molesworth, who also served as curator-in-residence at the Anderson Ranch in 2019, convinced Simpson to apply for the residency to take advantage of the art center’s large, walk-in kilns.

The Wheelwright retrospective and beyond

Simpson, who’s been represented by Chiaroscuro Contemporary Art in Santa Fe for most of her professional life, had her first mid-career retrospective at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in November 2018. Were it not for the birth of her daughter, Nugget, the exhibit would have opened a few years earlier, cementing Simpson’s place as the youngest artist to ever have a solo show at the museum. “I lost my youngest position to T.C. Cannon,” she says about the influential Kiowa art star whose life was cut short by a tragic car accident at the age of 31.

The Wheelwright show was the beginning of a new phase for Simpson that led to greater national interest in her work. “It’s changed my life,” she says. “I’m now represented by a gallery in San Francisco, the Jessica Silverman Gallery. It’s just nuts who I’ve been talking to and connecting with.”

If not for the Wheelwright show, it isn’t likely that she would have been selected for the exhibition at The School — or for the Anderson Ranch residency, for that matter. But Molesworth saw the show on a visit to Santa Fe with her wife, Susan Dackerman of Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center, and took notice. “She was like, ‘We thought we were in dreamy Santa Fe and your work was just good in context, but let’s let the Santa Fe wash off and then we’ll revisit the photos we took.’ When they sat down and looked at the photos, they were like, ‘No, it wasn’t just Santa Fe. She’s good.’ ”

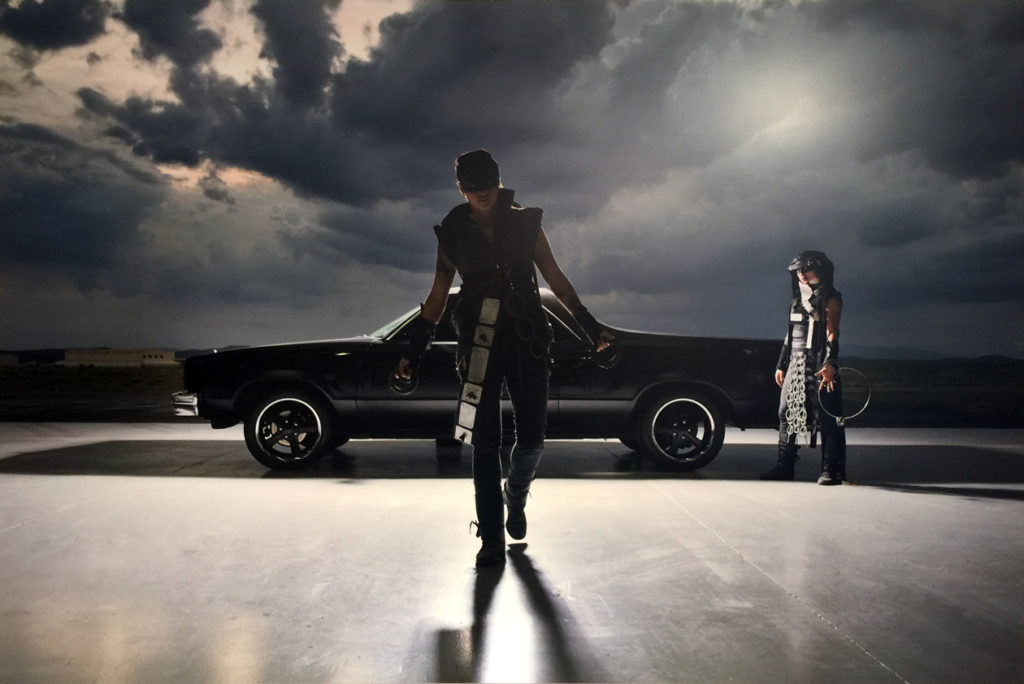

Simpson’s ceramics often betray the hand of the artist, whether she’s creating busts, full-sized figures of Native warriors, dolls, installations, or works in her Ancestor Masks series. She doesn’t try to disguise the fact that the pieces are clay; they’re usually dimpled with the impressions of the busy fingers that molded them. Her warrior figures, some of which were shown at the Wheelwright in her 2018-2019 solo exhibition LIT, are free from specific tribal associations, offering imaginative interpretations of what a warrior could be. Some of them are based, she says, on her idea of what tribes living in a post-apocalyptic future might look like. They’re mixed media works, painted with tribal designs of her own invention, and adorned with beads and jewelry made from metal and stone.

Many of her clay figures are female, but even so, the faces are anonymous, although they often bear a slight resemblance to her own rounded features, with tranquil, knowing eyes.

Dreams of speed and flight

With the award from the Women’s Caucus and a flurry of other exhibitions in the pipeline (including an upcoming fall show at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno), it’s hard to imagine that Simpson ever wanted to be something other than an artist. She was born into one of the most prominent families of Native artists in the country. In addition to her mother and her uncle Michael, other members of the family include ceramic artists Jody Folwell and Nora Naranjo Morse.

But when she was in high school, Simpson had other ambitions. “I really wanted to go into the Air Force. I used to make those plastic models of bomber planes and hang them from my ceiling. I wanted to fly so bad.”

She took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery test (ASVAB) and got high scores. Soon after, various branches of the armed services started calling. “My mom kept hanging up on them. She sat me down and was like, ‘You want to kill people?’ and I was like, ‘I just want to fly their airplanes, man.’ ”

Simpson hasn’t yet satiated that desire. She talks — sheepishly at first, then animatedly — of possibly taking advantage of a Whirly-Girls International flight training scholarship to learn how to pilot a helicopter. “You can do search and rescue and there’s a lot of side jobs you could do.” She even considered building one of her own, and having the tribe sponsor the project. “I could give the governor rides up the canyon,” she says, laughing. “I don’t know.”

If you know Simpson, you wouldn’t have any doubt that she could pull it off. In a room adjoining her studio is a photo of artist Jeff Brock’s souped-up 1952 Buick Super Riviera, Bombshell Betty, which broke several land-speed records at Utah’s Bonneville Speedway. Simpson practically seethes, recalling her obsession with Brock and how she wanted to break his record and become “the world’s fastest Indian.” Adjacent to her studio is the auto body shop where she works on her own custom cars. But Maria, her signature 1985 Chevrolet El Camino, isn’t there. The car, which she named after Native American potter Maria Martinez, sports black-on-black Pueblo designs in the style of San Ildefonso’s sought-after pottery. It’s currently on national tour, part of a traveling show called Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists.

Art as an act of healing the past

Simpson approaches the designs for her custom cars as she does all her art, with reverence and respect for her ancestry and empathy for the larger indigenous community. In part, that attitude is why she was selected for recognition by the Women’s Caucus for Art.

“I’ve known about Rose for some time but had never really seen her work in quantity,” says WCA president Margo Hobbs, who was impressed by what she saw at the Wheelwright. “It just blew me away. After, I was thinking that I should give her the President’s Award because everything she’s doing is right in line with what the Women’s Caucus, as an organization, supports.”

The award is specifically for a mid-career artist who embodies the organization’s mission, which, Hobbs says, is to create community through art, art education, and social activism. “It’s not just Rose’s work, which is so profoundly expressive, but the work she does with her community, with at-risk youth, and the various environmental organizations she’s involved with.”

For her May exhibition at The School, Simpson saw an opportunity to make a positive statement about a dark period in American history. The sculpture she’s working on depicts three youthful figures, standing back to back. At this early stage, they’re androgynous figures, and may remain so. They are meant to represent the souls of children from a bygone era, when Native youth were separated from their families, sent to boarding schools, and forced to assimilate into Western society.

The School was an abandoned schoolhouse that gallerist Shainman transformed into an art space. “Helen [Molesworth] was saying that when she first walked into the building, she could still hear the children’s voices in the walls,” Simpson says. “When I see it, I can’t help seeing a boarding school. Assimilation was a policy of genocide of indigenous people. It was a way to kill us. As a mother, I’m still struggling with it.”

Simpson speaks of how the abuse the children learned in boarding schools, particularly in the 19th century, contributed to persistent generational trauma and cycles of abuse. “This is what I’ve inherited and I’m trying to undo it,” she says, fighting back tears. “I’m 36 years old, I have a 3-year-old and I’m still dealing with what happened to my people in the 1800s. And it’s only one aspect of post-colonial stress disorder.”

But the clay figures aren’t really about the abuse. They’re about the bonds that children formed with each other in order to survive, and the communities they built together. “It’s the survival instinct,” she says.

Simpson’s work seems to come from a deeper place than ego can reach. She taps into a wellspring of the universal, to the core experiences of being human. It’s what makes her work accessible and relatable. “I’m dedicated to being aware all the time. What we do and why. What we ingest, through our eyes even, is what we become. How does different art affect us? What is the intention behind it? It’s pretty cool to have a space to build that conversation,” she says of the upcoming show. “I see it as an opportunity, an access point, for the art world to share consciousness.” ◀